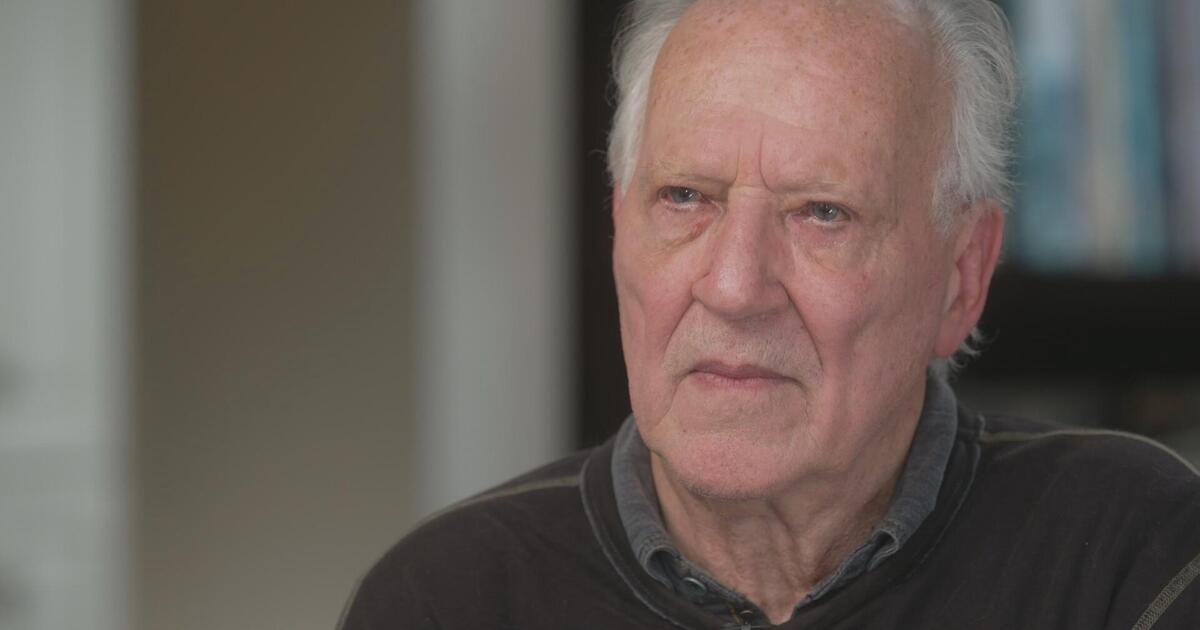

Werner Herzog may not be a household name but he is one of the most respected and unusual filmmakers of our time. Over the last six decades the German director has made more than 70 documentaries and feature films about everything from an unhinged cop in New Orleans, to a guy who thought he could live with Grizzly bears — he did, until they ate him. Werner Herzog has never shied away from the extreme, if anything, he is drawn to it. His movies are often dream-like explorations of the power of nature, the frailties of man, and the edges of sanity. At 82 he is still working constantly, still making movies no one else would or could ever dream of.

This was the film that introduced Werner Herzog to the world in 1972: “Aguirre, the Wrath Of God,” about a group of conquistadors searching for a lost city of gold in the Amazon, who gradually descend into madness.

Shot on a shoestring budget in Peru, it only got finished because of Herzog’s force of will and determination.

Anderson Cooper: I– I read that you sold your shoes in order to get– some fish to feed the crew.

Werner Herzog: Well, it’s not normally what a director has to do. It’s good to have some good boots, and you can barter it for a load of fish or my wrist watch I would give away. I would give away everything.

Anderson Cooper: And it’s worth it?

Werner Herzog: Of course. Of course it’s worth (laugh) it. I get away with the loot. I have a film.

Anderson Cooper: That’s the loot though. You’re not talking about making millions and millions of dollars. The loot, for you, is the film.

Werner Herzog: Yeah. And of course– I make money sometimes and I invest it in the next film.

If you’ve seen any of Herzog’s documentaries, it may be “Grizzly Man,” one of his most commercially successful. It tells the strange tale of Timothy Treadwell: an eccentric drifter who spent 13 summers in the wilds of Alaska recording himself interacting with grizzly bears.

Treadwell seemed convinced he had a spiritual connection with the grizzlies and was somehow their protector. In the end, he’s the one who needed protecting.

60 Minutes

We sat down with Herzog to watch the film, and others at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures David Geffen Theater in Los Angeles.

Anderson Cooper: You have a distinctly unromantic view of nature.

Werner Herzog: Yes. Nature is– is ab– utterly indifferent. We are not made to — become brothers with the bears. That happens in Walt Disney, not in– in real life.

In all of Herzog’s feature films and documentaries, you’ll find remarkable moments, nightmarish ones as well.

His curiosity has taken him to the remotest regions of our planet. With his distinctly teutonic tone, he narrates his documentaries himself. And asks questions that rarely have easy answers.

Herzog has revealed hidden landscapes under the Antarctic ice sheet, and apocalyptic oil fires in Kuwait after the first Gulf War. He’s risked his life to capture the power of volcanoes, and filmed ancient cave paintings in France rarely seen before.

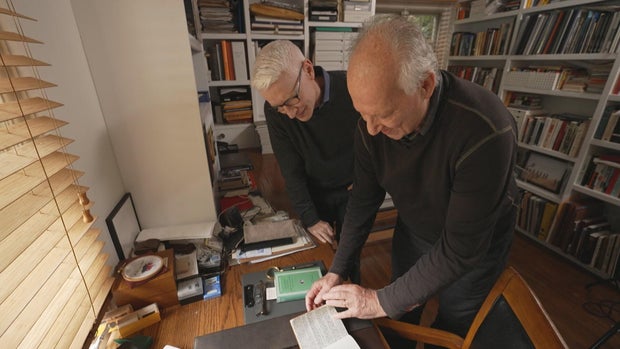

Herzog is now working on a new documentary in Los Angeles with his editor Marco Capaldo.

Werner Herzog: And now music.

Anderson Cooper: Wow.

Werner Herzog: Schubert’s…

It’s a movie about the search for a legendary herd of elephants in southern Africa. But Herzog insists it’s not a wildlife film.

Werner Herzog: It’s a fantasy of elephants. Maybe a search, like, for the white whale, for Moby Dick. It’s a dream of an elephant.

Herzog never had any formal training as a director. He was born in Munich just two weeks before the allies bombed it in 1942. His father was away serving in the German army when his mother fled with Werner and his older brother to the mountains of Bavaria.

Werner Herzog: We grew up in complete poverty and we had no running water, no sewage system, hardly ever electricity. We had one loaf of bread per week. And we were hanging at– at her skirt, wailing that we were hungry. And she spins around and she looks at us and she says, “Boys, if I could cut it out of my ribs, I would cut it out of my ribs, but I can’t.”

60 Minutes

Anderson Cooper: To this day, that experience–

Werner Herzog: To– yes.

Anderson Cooper: –shapes you?

Werner Herzog: Yes, it does.

Herzog didn’t see his first film until he was 11. He got hooked on American B movies like Zorro and decided filmmaking was his destiny. He just needed a camera. He finally found one in a film school in Munich.

Werner Herzog: One day I saw this camera room and nobody was in there, and I took one and tested it, walked out. And they never noticed that a camera was missing.

Anderson Cooper: I mean, that’s a stolen camera.

Werner Herzog: (sigh) It was more expropriation (laugh) than theft. You have to have– a certain amount of, I say, good criminal energy. (laughter)–

Anderson Cooper: To make a film–

Werner Herzog: Sometimes, yes, you have to. You– you have to go outside of what the norm is.

He’s been going outside the norm his whole life. In 1979 he began working on a fever-dream of a film called “Fitzcarraldo.” It took him three grueling years to make. German actor Klaus Kinski plays an obsessed Irishman who will stop at nothing to build an opera house in the Amazon.

To raise the money for it, Fitzcarraldo hatches a plan to harvest lucrative rubber trees in a remote jungle and hires indigenous laborers to haul a ship over a mountain to do it. Herzog refused to cut corners. He insisted on buying a 340-ton steamship and actually moving it up a mountain.

Anderson Cooper: Couldn’t you have used special effects with a model of a ship being moved over a mountain rather than actually moving–

Werner Herzog: Yes, it was–

Anderson Cooper: –an enormous–

Werner Herzog: A discussion with 20th Century Fox. And they said, we could shoot it in the botanic garden in San Diego. And we could move a tiny miniature boat. And I said, “No, we are not speaking the same language.”

Anderson Cooper: It certainly would’ve been easier,

Werner Herzog: No. It would have been a lousy film.

60 Minutes

That was the least of it. A border war forced Herzog to move the production a thousand miles away, to a new location. There were money problems, plane crashes, fighting between local indigenous groups, and constant battles against the rain and mud. Herzog’s relentless pursuit of his vision took a toll on the cast and crew and on him as well. Documentary filmmakers shot the chaos behind the scenes and turned it into a movie all its own, called “Burden of Dreams.” It’s just been re-released in theaters.

Werner Herzog (in “Burden of Dreams”): We are challenging nature itself and it hits back, it just hits back that’s all and that’s grandiose about it and we have to accept that it is much stronger than we are. Of course there is a lot of misery that is all around us. The trees here are in misery and the birds are in misery. I don’t think they sing, they just screech in pain.

Anderson Cooper: Did you feel that every day?

Werner Herzog: Every day, every night, and the next day, and the next night, and on.

Herzog also had to deal with Klaus Kinski, the star of the film, who was prone to explosions of rage.

Werner Herzog: I had– a madman as a leading character

Anderson Cooper: He had a temper.

Werner Herzog: As demented as it gets.

Werner Herzog: You had to contain him. And I– made his madness, his explosive destructiveness, productive for the screen.

Anderson Cooper: How do you do that?

Werner Herzog: Every gray hair on my head I call Kinski. (laugh)

Kinski appeared in five of Herzog’s films, and died in 1991, but not before putting his own thoughts about Herzog down on paper.

Anderson Cooper: This is what Klaus Kinski said of you in his autobiography, “I’ve never in my life met anybody so dull, humorless, uptight, and swaggering. Herzog is a miserable, hateful, malevolent, avaricious, money-hungry, (laughter) nasty, sadistic, treacherous, cowardly creep.”

Werner Herzog: Yes, it’s beautiful stuff, I actually helped him with–

Anderson Cooper: You helped him write this–

Werner Herzog: With a dictionary yeah, with Roget’s The– Thesaurus—

When “Fitzcarraldo” was finally released in 1982, Herzog won the best director award at the Cannes Film Festival.

Anderson Cooper: You must have been deluded to make this, or crazy in some way.

Werner Herzog: No, no, no. But the fact is when you look at the film industry, there is so much craziness around, so much– illusion, so much dementia, so much ego. And when I look at this, I know I’m the only one who is clinically sane.

Anderson Cooper: This– this shows you’re the only one who’s sane–

Werner Herzog: It shows it, yes, yes. (laugh) That’s my proof.

Herzog still has the journals he wrote while making “Fitzcarraldo.” Over the months as the pressure on him grew, his writing became barely readable.

60 Minutes

Werner Herzog: But it becomes microscopic almost.

He turned those journals into a book, called the “Conquest of the Useless.” He has published 11 others as well: fiction, poetry and memoirs.

Werner Herzog: I’ve always maintained since more than four decades that my writing, my prose and my poetry will outlive my films.

Anderson Cooper: You– you think your– your writing will outlive your films?

Werner Herzog: Yes, I’m totally convinced of that.

Herzog doesn’t just work behind the camera. Every now and then he acts. That’s him in the “Star Wars” series “The Mandalorian.” He’s also lent his distinctive voice to several characters on “The Simpsons.”

Last September we joined Herzog as he taught aspiring filmmakers on the Spanish island of La Palma off the west coast of Africa. It’s covered in volcanic rock and ash from an eruption three years ago — a Herzogian landscape if ever there was one.

It’s an 11-day workshop: less about the fundamentals of filmmaking, and more about poetic vision and grit.

60 Minutes

Werner Herzog: It’s his fantasies. It’s his ghosts that he’s searching.

He calls it a film school for rogues.

Werner Herzog: And for the rogues. I also say, you are able-bodied. Earn money to finance your first films. But don’t earn it with clerical works in an office. Go out and work as a bouncer in a sex club. Work as a warden in a lunatic asylum. Go out to a cattle ranch and– and learn how to milk a cow. Earn your money that way, in real life.

You do not become a poet by being in a college. And I teach them a few things like– forging– a shooting permit. “Can I have–” you see. It should look really authentic.

Anderson Cooper: How to fake a f– a shooting permit—

Werner Herzog: A shooting permit during a dictatorship.

Anderson Cooper: Have you made those?

Werner Herzog: Yes, of course. (laugh) And I teach lock picking. (laugh) You have to know– yes, you have to be good at that–

Anderson Cooper: Wait a minute. To make a film you have to know how to forge a permit and pick a lock?

Werner Herzog: Yeah. And you better carry bolt cutters everywhere. (Laugh) It’s not for the faint h– hearted.

Produced by Michael H. Gavshon. Associate producers, Nadim Roberts and Grace Conley. Edited by Daniel J. Glucksman.