Washington — The Supreme Court weighed Wednesday a yearslong court fight over South Carolina’s attempt to boot Planned Parenthood from its Medicaid program and whether beneficiaries can sue to enforce their ability to see their preferred health care provider.

South Carolina moved to withhold Medicaid funds from a Planned Parenthood affiliate in 2018, four years before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and left the issue of abortion policy to the states. But since that then, the landscape for abortion care has shifted drastically, with a dozen states enacting near-total bans on abortion and another four states, including South Carolina, outlawing the procedure after six weeks gestation.

While Planned Parenthood provides abortion services outside of Medicaid as allowed under state laws, anti-abortion rights groups and lawmakers at the state and federal levels have long been working to keep public health dollars away from the group. Its clinics also offer contraception, pregnancy testing, gender-affirming care and screenings for cancer and conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure.

The question in the case is a technical one: whether Medicaid beneficiaries can sue to enforce a provision of the Medicaid Act that allows them to seek care from the qualified and willing provider of their choosing. But if South Carolina prevails in the dispute, it could pave the way for more states to defund Planned Parenthood through their state Medicaid plans.

The court, which has a 6-3 conservative majority, appeared divided over whether Medicaid recipients can sue under a federal civil rights law to enforce the provision, known as the any-qualified provider requirement.

“We need something that’s out of the ordinary that signals to the federal court, this is not just something that the state must do, this is something that allows the individual to go into court and get enforcement,” Justice Samuel Alito said of a statute’s language.

But Justice Elena Kagan warned that if the Supreme Court were to accept South Carolina’s argument that a statute must include words such as right, privilege or entitlement in order to allow an individual to file a suit to enforce it, it is “changing the rules midstream.”

Nicole Saharsky, who argued on behalf of Planned Parenthood, told the justices that South Carolina is trying to disqualify a provider from its Medicaid program for reasons that are unrelated to its medical qualifications. It has been established that the state violated Medicaid patients’ ability to choose their own doctor, “the only question is whether she can do something about it,” she said.

“Congress expected that an individual would be able to sue in the rare instance when a state is keeping a needy patient away from a qualified and willing provider,” Saharsky said. “If the individual can’t sue, this provision will be meaningless.”

The legal battle over Planned Parenthood’s funding in South Carolina began in July 2018, when Gov. Henry McMaster issued an executive order directing the state’s health department to deem abortion providers unqualified to provide family-planning services under Medicaid and terminate enrollment agreements.

Federal law prohibits Medicaid from paying for abortions except in cases of rape or incest, or to save the life of the mother. But the state argued that because money is fungible, giving Medicaid dollars to abortion providers frees up other money to provide the procedure.

The South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services notified Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, which has clinics in Charleston and Columbia, that its provider agreements were being cancelled because it was no longer qualified to provide services to Medicaid recipients.

Planned Parenthood South Atlantic offers prenatal and postpartum services, as well as cancer screenings, physical exams and screenings for health conditions and cancer. But the state says that there are more than 140 other federally qualified health clinics and pregnancy centers across South Carolina who accept Medicaid and can provide services to low-income patients.

Nearly 20% of South Carolina residents are insured through Medicaid, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, and 25% of its residents live in medically underserved areas.

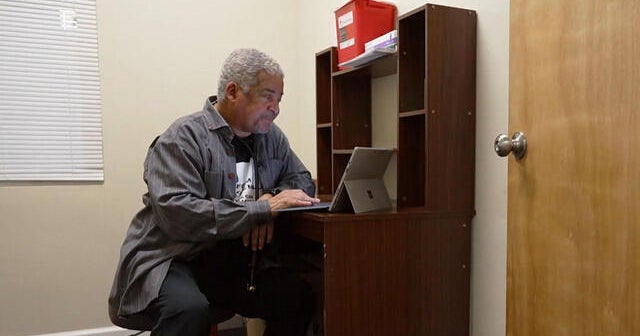

After Planned Parenthood was disqualified from participating in South Carolina’s Medicaid program, Julie Edwards, a patient who received health services from the Planned Parenthood affiliate, and the organization filed a lawsuit challenging the state’s termination decision.

Edwards alleged in her lawsuit that the state’s cancellation of Planned Parenthood South Atlantic’s agreement violated her right to choose her provider under the Medicaid Act and asked a federal district court to issue an order allowing her and other patients to continue receiving care from Planned Parenthood.

The district court sided with Edwards, finding that Medicaid patients can sue to obtain health care services from their preferred qualified and willing provider. The court also held that South Carolina likely violated the any-qualified provider requirement by terminating Planned Parenthood’s participation in the state Medicaid program without cause.

A federal appeals court on numerous different occasions concluded that Edwards’ had a right to sue and blocked South Carolina from excluding Planned Parenthood from its Medicaid program. The Supreme Court agreed in December to take up South Carolina’s appeal.

Defenders of South Carolina’s move have argued that states are better suited to decide where to spend the Medicaid dollars they receive from the federal government, which they said leads to better treatment for low-income patients and their families.

“You’ve got roughly 200 publicly funded health care clinics in South Carolina that provide a broad range of high-quality health care services, including family-planning services,” said John Bursch, a lawyer with the Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative legal group. Bursch is arguing on behalf of South Carolina at the Supreme Court.

He continued, “South Carolina is entitled to decide that there are better options, and that’s exactly what it’s done.”

Bursch told the justices during oral arguments that Congress knows how to write legislation that clearly grants a private right that can be enforced through the courts, as it has done so in other statutes. But the provision at issue in the case involving Planned Parenthood doesn’t use the word “right” or similar words like “privilege” or “entitlement.”

“If there is any ambiguity in this context, the state has to win because it’s not put on notice of when it might be sued,” he said. “At the end of the day, putting states on clear notice requires explicit rights-creating language.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh said that the goal is to provide clear guidance for courts to follow.

“I’m not allergic to magic words because magic words, if they represent the principle, will provide the clarity that will avoid the litigation that is a huge waste of resources for states, courts, providers, beneficiaries and Congress,” he said.

Several states have taken steps to block Planned Parenthood from receiving Medicaid funding, including Texas, Mississippi, Missouri and Arkansas. Two federal appeals courts, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit, ruled that Medicaid patients do not have a right to sue over the state’s decision to exclude Planned Parenthood from states’ Medicaid programs.

But several other appeals courts have blocked state efforts to cut off the organization from Medicaid dollars. If the Supreme Court rules for South Carolina, it would clear the way for more states to exclude Planned Parenthood from their Medicaid programs.

“The reason why they would do that is pretty simple,” Bursch said. “Many Americans don’t want their tax dollars propping up the abortion industry, especially when those dollars can be better spent on real health care.”

But Saharsky said that Congress’ goal when writing the law was to stop states from excluding Medicaid providers from their programs arbitrarily, which she said South Carolina is doing with its effort to stop Planned Parenthood from receiving public health dollars. While Saharsky noted that a state would receive significant deference if it disqualified a provider from its Medicaid program because of questions of medical competence, she said that is not what is at issue in this case.

“It is only that there is something Planned Parenthood is doing outside of Medicaid that the state wants to disqualify it from the program,” she said.

Kagan warned that if states were allowed to provide their own justifications for terminating Medicaid provider agreements without the potential for recourse by patients, it would pave the way for states to “split up the world by providers.”

“That does not seem what this statute is all about, is allowing states to do that and then giving individuals no ability to come back and say, ‘that’s wrong. I’m entitled to see my provider of choice regardless of what they think about contraception or abortion or gender-transition treatment,'” she said.

Before the arguments, Amy Friedrich-Karnik, director of federal policy at the Guttmacher Institute, a pro-abortion rights research organization, said at stake in the case is the ability of Medicaid beneficiaries to get the health care they need from the provider they know and trust.

“A loss in this case not only means that Medicaid patients in South Carolina would be unable to access Planned Parenthood, the ripple effect of that could mean that Medicaid patients across the country and particularly in states that might be inclined to want to restrict Medicaid recipients’ ability to get care, it could affect all of those folks, and it fundamentally affects their ability to access really needed reproductive health care services that Planned Parenthood provides,” she said.

Friedrich-Karnik also said that a win for South Carolina would encourage the Trump administration to urge states to kick Planned Parenthood off state Medicaid plans.

“It emboldens the federal government, and it emboldens state governments who would like to restrict people’s access in this way to do so,” she said.

The Trump administration is backing South Carolina in the case and warned that a decision affirming the lower courts would invite a flood of litigation as beneficiaries seek to enforce other provisions of the Medicaid law and other statutes.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett questioned what would flow from a ruling that allowed Medicaid recipients to bring lawsuits to enforce the any-provider provision.

“We’re here because of Planned Parenthood not being a qualified provider in South Carolina, but would this open the floodgates of people bringing” lawsuits because they can’t see the provider of their choice, she asked Kyle Hawkins, counselor to the solicitor general, who argued for the federal government.

Separately, Project 2025, the policy blueprint overseen by the conservative Heritage Foundation, calls on the Department of Health and Human Services to limit Planned Parenthood’s funding through Medicaid in part by issuing guidance reemphasizing that states can strip the group of its public dollars in state plans.

A decision from the Supreme Court is expected by the end of June.