A lucky group of scientists were able to explore a never-before-seen part of the Antarctic after an ice shelf broke, revealing newly exposed seafloor and a previously inaccessible ecosystem hundreds of meters beneath the surface.

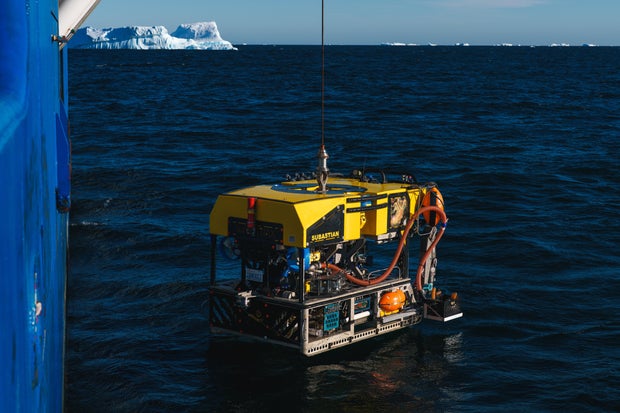

A team from the Schmidt Ocean Institute were aboard the “R/V Falkor (too)” research vessel in January 2025 when a piece of ice the size of Chicago broke off from the George VI Ice Shelf, a floating glacier 57 miles away.

“This is unprecedented, to be able to get there so quickly,” executive director of the Schmidt Ocean Institute Dr. Jyotika Virmani told CBS Saturday Morning. The institute is a philanthropic foundation that sponsors ocean exploration and science research.

Alex Ingle / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Dr. Patricia Esquete, the lead scientist aboard the vessel, said there was no debate about whether or not to go to the site.

“We were like ‘Oh my God, I cannot believe this is happening,'” Esquete said. “Everybody agreed that we had to go there.”

In just a day, the vessel was able to arrive at the area. They lowered a submersible robot more than 1,000 meters underwater so that it could explore the area and livestream the region to the scientists.

Alex Ingle / Schmidt Ocean Institute

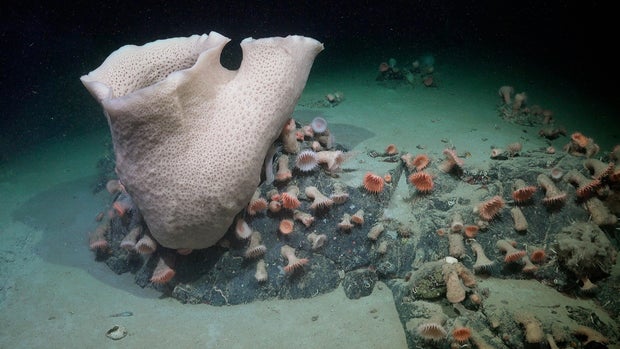

Almost immediately, the researchers started seeing things that humans had never laid eyes on before.

“The first thing we saw was a huge sponge with a crab on it,” Esquete said. “That’s already quite amazing, because one question that we had is ‘Will there be any life at all?'”

Sponges grow very slowly — sometimes less than two centimeters a year. To get this big, the scientists say, the ecosystem has been thriving for a long time — possibly even centuries.

ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

The remotely operated vehicle explored the seafloor for eight days, the institute said. It also discovered large corals and more sponges, which were supporting species including icefish, giant sea spiders and octopi.

Esquete said that researchers are now studying how the ecosystem has been getting enough energy to function. Virmani suggested that ocean currents could be bringing nutrients to the area.

Since January, scientists have confirmed the existence of at least six new species, Virmani said, but there are “many more yet to be analyzed.”

Alex Ingle / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Because Schmidt Ocean Institute makes all of its research, data and livestreams open access, the information is available for other scientists to explore and analyze.

The team’s research into the new ecosystem isn’t remotely finished, Esquete said. They plan to return to the area in 2028.

“The Antarctic is changing rapidly,” Esquete said. “And in order to understand what was going to happen, we really need to come back and keep studying and keep trying to learn and understand what was driving that ecosystem under the ice shelf.”

ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute